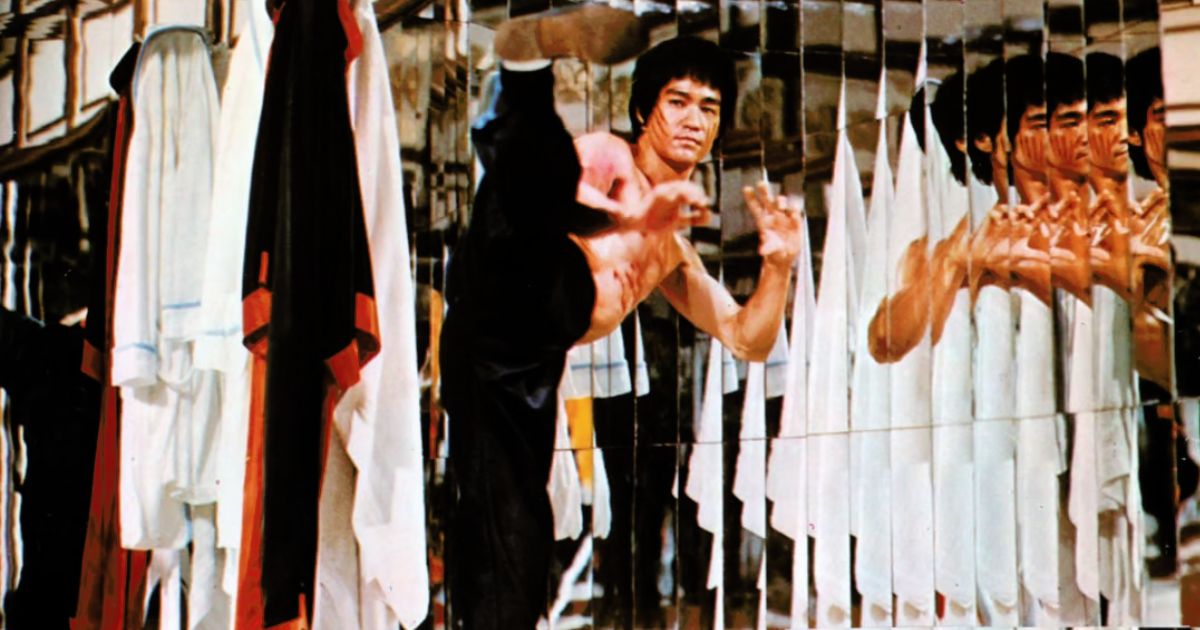

As the 50th anniversary of martial arts icon Bruce Lee’s death approaches, a new documentary investigates a bizarre phenomenon that erupted in the wake of the Little Dragon’s untimely passing.Enter the Clones of Bruce, directed by documentarian and film preservationist David Gregory, charts the wave of low-budget kung fu films that emerged from Hong Kong almost immediately after Lee’s death, starring a slew of imitators in a subgenre known as Bruceploitation.At the time of his death, on July 20, 1973, Lee had completed just four martial arts films. The last of these, the US-Hong Kong co-production Enter the Dragon, would be released a month later and became a smash hit around the world.The film cemented Lee’s status as the face of the genre, and created an unprecedented explosion of interest in kung fu cinema.

Now this new-found global audience demanded more, and as producers went in search of the next Bruce Lee, their less than scrupulous contemporaries took a faster and cheaper path: as-yet-unestablished martial artists were dressed up to look like Lee, and rechristened Bruce Li, Bruce Le, Dragon Lee, or Bruce Liang in titles that deliberately evoked Lee’s earlier hits.While Lee’s family and Golden Harvest – the studio that made him a star – could do little more than stand idly by, a torrent of films were rushed into theatres.

What Gregory’s film attempts to do, however, is reappraise these works, document the different ways they capitalised on Lee’s legend, and find value in them today. Crucially, the film also features candid, sometimes emotional conversations with the actors themselves, and how their time emulating – or ripping off – Bruce Lee has affected their lives.

Convincing Lee’s on-screen clones to participate wasn’t always an easy task, and required a good deal of persuasion from Gregory and his fellow producers, expert on Hong Kong cinema Frank Djeng, and Michael Worth, author of The Bruceploitation Bible.Gregory spoke to the Post in an interview earlier this month about his labour of love, which he began filming in 2016.

“What took so long was that I was holding out for Bruce Le,” Gregory says, referring to Burmese-born martial artist Wong Kin-lung, whose debut in the genre was in The Big Boss Part 2 (1976), which continued the adventures of Lee’s character.“He was the most prolific, and without him I felt it would never be complete. Eventually we started editing the film without him. When we showed him the cut, only then did he agree, so I hightailed it back to Hong Kong.”While many different actors became Bruce “clones” or adopted roles that were seen as mimicking his style, Le was one of four performers responsible for the bulk of the output.

Another notable impostor was Bruce Liang, aka Leung Siu-lung, whose credits include The Dragon Lives Again (1977), a wacky fantastical comedy adventure that follows Bruce Lee into the underworld, where he must battle such foes as Count Dracula, Zatoichi and James Bond.More recently, Leung appeared in Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s Kung Fu Hustle and the low-budget hit Gallants, which respectively won best picture at the Hong Kong Film Awards in 2005 and 2011.South Korea’s Moon Kyoung-seok appeared under the names Bruce Lei, Bruce Rhee and most famously Dragon Lee during his prolific tenure as a Lee clone, which included The Real Bruce Lee (1977) that inserted documentary and early screen footage of the real actor into a heavily re-edited Korean martial arts film.

Much like Le, he was initially reluctant to speak with Gregory’s crew. “When we got to his office, he apparently had no idea we were coming, and I got the sense he thought we were there to make fun of him,” Gregory says.“But as time went on, and we obviously knew a lot about his career, he really warmed up to us.”Bruce Li, the last of the big four, appears most openly regretful of his role in this exploitation movement. Born Ho Chung-tao in Taiwan, he came to Hong Kong to become a stunt man, before assuming the mantle of Lee in the likes of Super Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1974), Goodbye Bruce Lee: His Last Game of Death (1975) and many more such films.

“There seems to have been a lot going on that he was unaware of,” Gregory concedes. “Li would agree to do one project so that he could show jeet kune do and pay tribute to Bruce Lee, but it never seemed to turn out the way he envisaged.“But he was in 40 of these movies, so it’s not like he was completely in the dark.”This seems to have been a common issue within the movement – that even the actors and directors were being exploited by greedy producers who would recut and reuse in multiple films footage for which they had paid only once.

Actors who bore no resemblance whatsoever to the late martial arts star were cast in Bruce Lee-like roles. Japanese actor Yasuaki Kurata was credited as Bruce Lo, apparently without his knowledge, while African-American fighter Ron Van Clief was branded the Black Dragon, a blaxploitation-style reincarnation of Lee.Gregory’s biggest single challenge was tracking down the films themselves.“There’s so little archival 35mm material of these films,” he explains. “The Hong Kong Film Archive had only The Dragon Lives Again. The Taiwan Film Archive in Taipei had a couple of prints, but they were in such bad condition it was unbelievable.”

After their original run in cinemas, the films were transferred to video, after which it seems that the prints were simply destroyed.For Gregory, whose company Severin Films is dedicated to the preservation and restoration of grindhouse and genre cinema from around the world, this situation is difficult to accept.“I asked pretty much everybody: why are there no film elements for these films?”, he says, referring to the physical films such as reels and negatives.

The answers he got were less than encouraging. “Hong Kong is very small, film prints are very big. Once the films were transferred onto tape and they got their TV master, they threw that s*** in the water. It was gone. That shows you the value they held of these films.”Fortunately, while the birthplace of these films may have failed Gregory and his team, usable prints have been discovered and acquired for a number of these underground oddities.“I’ve no idea if there’s an audience for Bruceploitation,” says Gregory, after admitting that this is his most expensive documentary yet, “but here we are, 45 years later, still talking about these movies, so let’s give it a shot.”Enter the Clones of Bruce has its Asian premiere at the Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival in South Korea in July 2023, alongside a new 50th anniversary restoration of Enter the Dragon.

Post navigation

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Uncategorized10 months ago

Uncategorized10 months ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago