At the Golden Globe awards ceremony, tempers are beginning to fray. An enormous man with an impossible name and a wide, self-satisfied grin has picked up the prize for Best New Talent of 1977.

The man on the next table, also muscle-bound, is up for Best Actor and Best Screenplay awards. His name is Sylvester Stallone and he doesn’t win either of them. ‘Jesus, this is a nightmare,’ Stallone growls.

He can’t stop glaring at his rival Arnold Schwarzenegger, so smug about his trophy for a film no one cares about, the comedy Stay Hungry.

Stallone is here for Rocky. That film is his passion project. He dreamed it up, he wrote it, he found backers, he starred in it and now he ought to be basking in its glory. It should be him, the centre of attention with the thousand watt smile, accepting congratulations from Barbra Streisand, Laurence Olivier and the rest of them tonight.

Finally, Rocky earns an award. It’s a big one, Best Drama. But the moment is ruined for Stallone when Schwarzenegger locks eyes with him. And he’s still smiling.

Stallone lunges. He grabs the giant bowl of roses on the centre of his table, lifts it over his head and with his shoulders almost splitting his dinner jacket, hurls it at Schwarzenegger.

The bowl smashes across the hotel carpet. Everyone in the room gasps. And the War of the Roses on Steroids is launched.

Hollywood didn’t understand it yet but these two newcomers were the future of the movie industry. This seemed incomprehensible to studio bosses who expected leading men to be suave, conventionally handsome and wry.

Stallone had a highly expressive face, with soulful eyes and sensuous lips, but no one had ever called it conventionally handsome.

When he was born in New York in 1946, the doctor clamped forceps on to his head as he emerged and pulled too hard, severing a facial nerve above his jaw.

The injury affected the way he spoke. ‘Reminiscent of the guttural echoings of a mafioso pallbearer,’ he once joked of his gravelly, slightly slurred voice. It also made the left side of his face droop a little. At school, kids taunted him with nicknames ‘Slant Mouth’ and ‘Mr Potato Head’.

Arnie was born a year later in the Austrian farm village of Thal. His father Gustav was an ill-tempered man who had been a member of the Nazi party and was left racked with anger and guilt when Hitler’s regime was toppled. Gustav would frequently unleash these emotions on his two children. ‘My hair was pulled. I was hit with belts,’ Schwarzenegger remembered five decades on.

Far from being mocked at school, though, he could charm anyone – including the occupying American soldiers. Each morning a US armoured car equipped with 40mm cannons would stop outside his family’s cottage and take him to school.

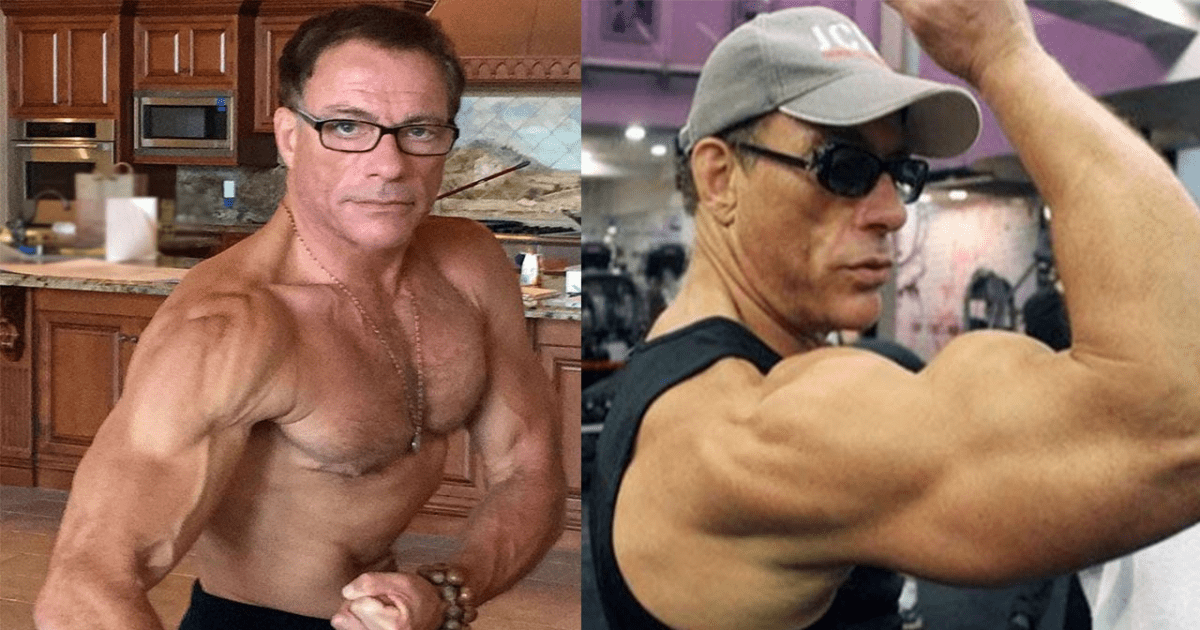

The regular beatings made him determined to prove he could absorb any pain and grow stronger, like iron on the blacksmith’s anvil. He wrote down a mantra – ‘Arnold, you are a winner’ – and repeated it aloud a dozen times a day. Eating any meat he could find, he gorged on ‘Arnold’s Protein Burgers’ – bull’s testicles.

By the time he arrived in America in 1968, he had already won the Mr Universe title at the age of 20. Movie director Arthur Seidelman met him in a Manhattan coffee shop and was astonished by his appetite: ‘He had a massive breakfast. Four eggs, two baked potatoes and two waitresses,’ he recalled. The following year, after living all over the East coast, Stallone moved back to New York. He, too, had endured a tough childhood, expelled from a series of schools and, at one of them, voted ‘student most likely to end up in the electric chair’.

He slept on a bus station bench with his paltry possessions in a locker and spent every day tramping the streets, looking for a break. His first appearance was in a soft porn film, The Party At Kitty And Stud’s, which took two days to shoot and featured a nude game of ring a ring o’ roses. The film featured his first action sequence, with him leaping over a fence in New York’s Central Park. The $200 fee got him out of the bus station but attempts to find an agent were all met with the same response: ‘There’s no call for your type.’

As well as taking any part he could, Stallone worked as a theatre usher, bouncer and fishmonger. In every spare moment, he wrote screenplays, often under fake names such as Q Moonblood or JJ Deadlock.

One script was called Cry Full And Whisper Empty In The Same Breath. Another, called Sad Blues, was about a rock star with an illness that could only be cured by bananas. It ended with the singer dying onstage mid-gig.

Spray-painting the windows of his apartment black to remove distractions, he wrote six half-hour TV pilots in a 14-hour session.

When none sold, he started work on what he called a ‘vile, putrid, festering little street drama about a good guy surrounded by rotten people’. The good guy’s name was Rocky Balboa. United Artists offered to make the movie if they could get Burt Reynolds or Ryan O’Neal to star.

Stallone insisted he had to play the lead.

The studio tried to back out but eventually proposed a feeble budget of $1 million (about £4.4 million today).

Stallone started waking at 4am, spending days in the gym, punching bags until his knuckles bled and his thumbs bent back, determined to look like a convincing boxer.

Rocky became the biggest movie of 1976, grossing £92 million in the States alone – more than its Oscar rivals Taxi Driver, Carrie and Network put together. The era of the muscle man hero had arrived. Schwarzenegger had a similar attitude to achieving fame. After he grappled with a bear in the 1970 film Hercules In New York (in which he was billed as Arnold Strong), he growled to a friend: ‘I saw an agent just now. He doesn’t like my body. He doesn’t like my name. And he doesn’t like my accent. But f*** him – I’m going to be a superstar.’

Real stardom didn’t arrive until 1982, with the swords- and-sorcery epic Conan The Barbarian.

Promoting that movie, he told reporters he liked to see himself on a scale of one to ten, with one being a ‘normal man’ and ten being a ‘superhuman’. ‘Now I’m an eight, so I have two more steps to go,’ he said.

‘I would pay anything for my father to be alive again for just one hour, to see what I’m doing today,’ he added of the man whose funeral he had declined to attend in 1972. His fee for Conan was $1million but that wasn’t enough – because Stallone was commanding three times that.

Sly was also making enemies with his insistence on having everything his own way.

He agreed to play a gangster in the Jazz Age drama The Cotton Club but tore up the contract when the studio refused to rewrite the script to make his character more sympathetic.

Former Paramount boss Robert Evans sent him an open letter: ‘Your deportment in our relationship both personally and professionally I find repugnant and ill-mannered and, concerning you, most self-destructive.’ Even Dolly Parton, despite praising his kissing skills, said less than flattering things too.

‘Sly is the perfect balance of total ego and total insecurity,’ she said. ‘I always told him he was spectacular but that he had a blind spot where compassion and spirituality ought to be.’ During filming for the Rambo sequel First Blood Part II he hired a bodybuilding coach and spent eight months jacking up his physique, training four hours a day and taking courses in archery and survival while living on chicken.

By the time filming started in Acapulco, Mexico, his body was a chiselled edifice of musculature. But he was also partying so hard he acquired the nickname ‘Mayor of Acapulco’ for driving between the city’s discotheques in a limo dubbed the Sly Mobile. Schwarzenegger’s limo was a custom-built black Jeep Wagoneer with a colossal 6.6-litre Duramax diesel engine and an exhaust pipe as thick as his arm.

The leather upholstery was festooned with feathers.

Under the bonnet was a powerful speaker that blasted out a warning in Arnie’s distinctive accent: ‘Hey! Idiot! Get out of the road!’

Arnie responded to the success of Rambo with the sci-fi blockbuster Terminator, in which he had just 14 lines of dialogue – including its defining catchphrase, I’ll Be Back.

He followed that with Commando as a vengeful father hunting down the men who have kidnapped his daughter, killing them one by one.

Producer Joel Silver hired Mark L Lester to direct the movie. He and Arnie met at a party at the Playboy mansion. ‘We were sitting next to each other in pyjamas,’ Lester remembers. ‘He said, “Want to do my next movie?” I said, “Can I read the script?” He said, “No – if you read the script, you’ll never do the movie”.’ Lester introduced Schwarzenegger’s character John Matrix with a shot in which he strides out of a wood with a chainsaw in one hand and an entire tree over his shoulder.

The image was inspired by the 1930s films of Germany’s Leni Riefenstahl. Lester said: ‘Even though they were Nazi films, they had some amazing film-making in them. It was to make Arnold seem strong and powerful.’

According to rumours, the script was rewritten to ensure Commando’s body count was higher than Rambo’s. Schwarzenegger embraced the chaos that ensued as Matrix destroyed his foes using a four-barrelled rocket launcher, a machine gun, hand grenades and even some gardening equipment he found in a shed.

In fact, the star had his own idea for a kill: inspired by a World War I story he’d heard. Schwarzenegger suggested that Matrix could chop off an enemy’s arm with an axe, then slap him with the severed limb to make him stop screaming – with the line, ‘Quit whining!’

When Rambo is asked in First Blood what brings him good luck, he points to his giant Bowie knife with a serrated nine-inch blade and says, ‘I guess this.’

When Matrix unsheathed his Commando blade later the same year, it was half an inch longer. Three years later, as well as wielding grenade launchers, flame-throwers and AK-47s, Rambo still had his Bowie knife. But now it was two inches longer.

Stallone accepted competition from no one, not even children. On the set of Rambo III, director Peter MacDonald cringed at a faux pas by Doudi Shoua, nine, who played Rambo’s Afghan sidekick Hamid. ‘This kid was annoying, he could drive you crazy,’ said MacDonald. ‘But he was full of life and energy. I’m doing a tracking shot with him and Sly with quite a bit of dialogue, and Sly gets his lines wrong.

The kid picked him up and told him the right line. Now I’m looking at Sly and thinking, “This is not going to work too well”.’

A short while later, a producer approached MacDonald and said, ‘Sly’s had a great idea. The kid’s got to die.’ MacDonald replied: ‘In the film or in reality?’

After Ronald Reagan declared himself a Rambo fan, the rivalry between Stallone and Schwarzenegger burned white hot.

In a Playboy interview, Arnie scoffed at his rival’s highly publicised insistence on travelling with a security team in case he was targeted by anti-American terrorists: ‘I think a lot of times this bodyguard stuff is a show,’ he said.

He added: ‘He is not my friend, he just hits me the wrong way. I make every effort humanly possible to be friendly to the guy but he just gives off the wrong vibrations.’

Despite Schwarzenegger’s fondness for Cuban Davidoff cigars, he refused to back Stallone’s scheme for an all-male smoking club, saying that he disliked sexism. He also disliked Sly’s jewellery and his dress sense, once complaining about his rival’s ‘f***ing fur coat’.

Stallone was so incensed that when he walked into a New York bar and saw a picture of Arnie on the wall, he ordered the bartender to take it down. There were attempts to broker a truce, even to put them together in a film. Schwarzenegger claimed Stallone had offered him the villain role in the police thriller Cobra but that he turned it down: ‘I didn’t think I would be done justice, so I stayed away from it.’

The film studio which had a deal with both stars arranged a sit-down with them for a project called Bartholomew vs Neff. It was an uneasy affair. ‘Everybody was tense,’ recalls producer Mario Kassar.

‘I managed to get them to come to my house but the whole thing was, “Who’s coming first and who’s coming second?” It was a very funny screenplay, about two neighbours who hated each other. But after the meeting, it was history.’

Instead, Schwarzenegger played a prank, leaking rumours that he was desperate to land the lead role in a big budget comedy about a tough guy cop whose mother moves into his apartment.

The reality was that Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot was a stinker and everyone knew it – except Stallone, who called in every favour to be cast instead of Arnie.

‘He totally went for it,’ Schwarz- enegger gloated. ‘A week later I heard about it: “Sly is signing now to do this movie”. And I went, “YES!”.’ The result bordered on unwatchable. The movie, unanimously panned by critics, is a succession of excruciating scenes where Stallone looks desperately uncomfortable.

Too late, the star realised he’d been tricked, calling it, ‘the worst film I’ve made by far, maybe one of the worst films in the entire solar system, including alien productions we’ve never seen. A flatworm could write a better script.’ But by then, the feud was fading, conquered by the only thing that matters more in Hollywood than ego: money.

Schwarzenegger was approached in 1990 by a businessman with a vision for a chain of restaurants with a movie theme, where people could have a taste of Hollywood glamour. They would be affordable but would glitter with stardust, filled with iconic props and occasional cameos from A-listers.

Schwarzenegger nodded his way through the presentation. ‘Count me in,’ he said. Bruce Willis was quick to sign up and, when Warren Beatty turned it down, Stallone decided he wanted a seat at the dining table. ‘I begged,’ he admitted later. ‘They saw me outside on my knees saying, “Please!”.’

It seemed obvious, very quickly, that Café Hollyrock was going to be huge. Especially when it changed its name to Planet Hollywood.

A few weeks later during the Cannes Film Festival in the South of France , the truce was sealed. At the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc, the band Gipsy Kings performed at a $1million soiree for guests including Jean-Claude Van Damme, Dolph Lundgren, Sharon Stone and Clint Eastwood. Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall danced on a table top.

Halfway through the evening, Stallone and Schwarzenegger arrived together.

Arnie, wearing a Hawaiian shirt, appraised the terrace like a Terminator scanning a biker bar. Sly, in a button-up shirt, blazer and designer sunglasses, did the same.

And then, to the amazement of all, the pair turned to each other, locked hands, and started to dance. The superstar crowd looked on, delighted. They were present for a monumental moment, two colossal egos finally aligning in perfect harmony.

Then, abruptly, Stallone grimaced and stopped. ‘Godammit,’ he told Schwarzenegger. ‘You’re leading. I hate that.’

Adapted from The Last Action Heroes: The Triumphs, Flops And Feuds Of Hollywood’s Kings Of Carnage, by Nick de Semlyen, published by Picador.

Post navigation

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Uncategorized11 months ago

Uncategorized11 months ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment12 months ago

Entertainment12 months ago

Uncategorized9 months ago

Uncategorized9 months ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year ago